Dukh-i-zhiznik Singing Compared in Russia and America1989-1994 research by Dr. Mazo |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| FAITH |

SONGS,

BOOKS

|

HOLIDAYS |

PROPHETS | COMMUNION | FOUNDED | |||||

| Bible |

Borrowed2 |

Dukh i zhizn' | Christ's | God's | Yes |

No |

Open |

Closed |

Year |

|

| Molokan |

X |

3 |

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

~1765 |

| Prygun |

X |

X |

|

X |

X | X |

|

|

X |

~18336 |

| Dukh-i-zhiznik1 |

X |

X |

X4 |

– | X |

X5 |

|

|

X |

~1928 |

1. Founded in America. All Maksimisty are Dukh-i-zhizniki, but not all Dukh-i-zhizniki are Maksimisty.For background on the evolution of these faiths, see: Conovaloff, Andrei. "Taxonomy of 3 Spiritual Christian groups: Molokane, Pryguny and Dukh-i-zhizniki — books, fellowship, holidays, prophets and songs,"source of the table above. Dr. Mazo did not have this Taxonomy during her research, and though she was aware of major differences among the faiths, she had no easy way to label them, so reverted to a "catch-all" general term, probably derived from malakan.

2. Most adapted from Russian folk songs and borrowed from German Protestants.

3. Not during service, but often during meals at weddings, funerals, child dedication, holidays

4. Open canon, a sacred text that can be modified by continuous revelation through their prophets.

5. Each congregation has 1 or more prophets. There have been at least 200 prophets since 1928 in all congregations around the world. Prophecies of only 4 prophets were published in their Kniga solnste, dukh i zhizn' (1928 holy book in Los Angeles). Over 100 prophesies are written in secret notebooks shown only to trusted believers.

6. Reorganized in Taurida Governorate, named in 1856 in the Caucasus.

Edited original article.

Singing as Experience among

Russian American Molokans

Dukh-i-zhizniki

Margarita MazoSECTIONS

By Way of Historical Introduction

By Way of Historical Introduction- The Role of the Spiritual

- Support System—Zakon [the

law]

- The Role of the Verbal

- The Communal Worship and "Church Jobs"

- The Power of Singing

- Transformations

of Singing during Sobranie [prayer meeting]

MolokanPsalms: Transmission, Formal Features, and Performance Practices- Comparison of American and Russian Singing

- Keeping Russian Melody versus Russian Language

- Resettling the Culture

- By Way of Conclusions

- Postscript

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Molokan

Sobranie seating

arrangement.

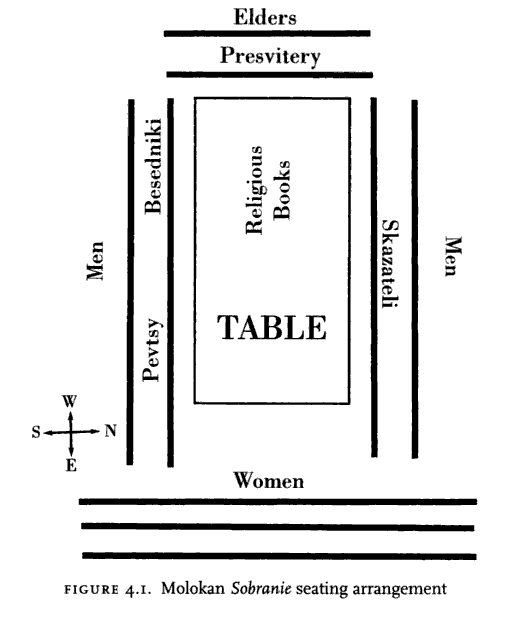

- Ya skazal pri polovni dnie moikh (I Said in the Cutting Off of My Days.) Isaiah 38:10, Comparison of A Russian and American versions of the psalm recorded in 1990.

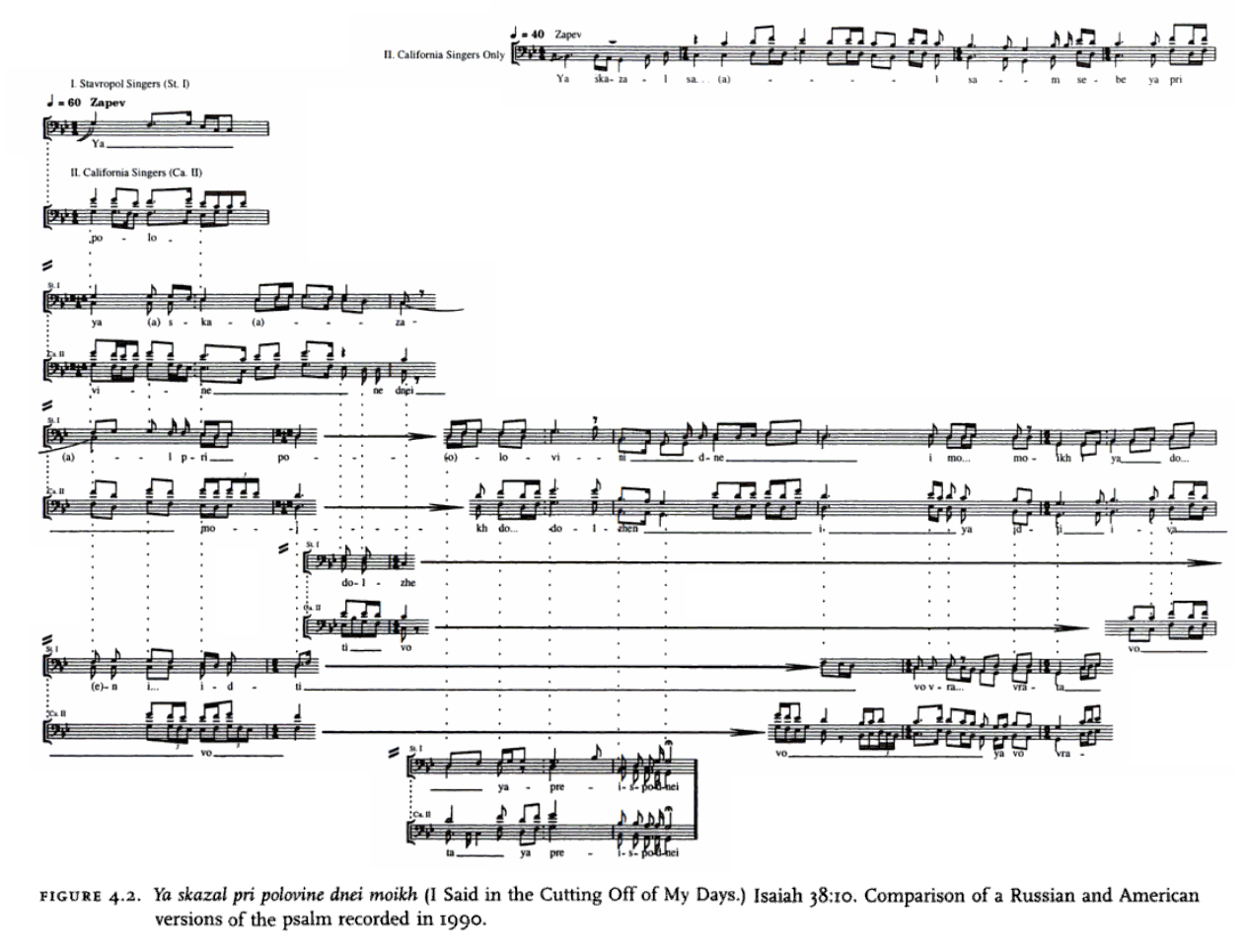

- Don Cossack protyazhnaya song transcribed by Alexander Listopadov in 1900 in a Don Cossack village Yermakovskaya (Listopadov, 1906, 214).

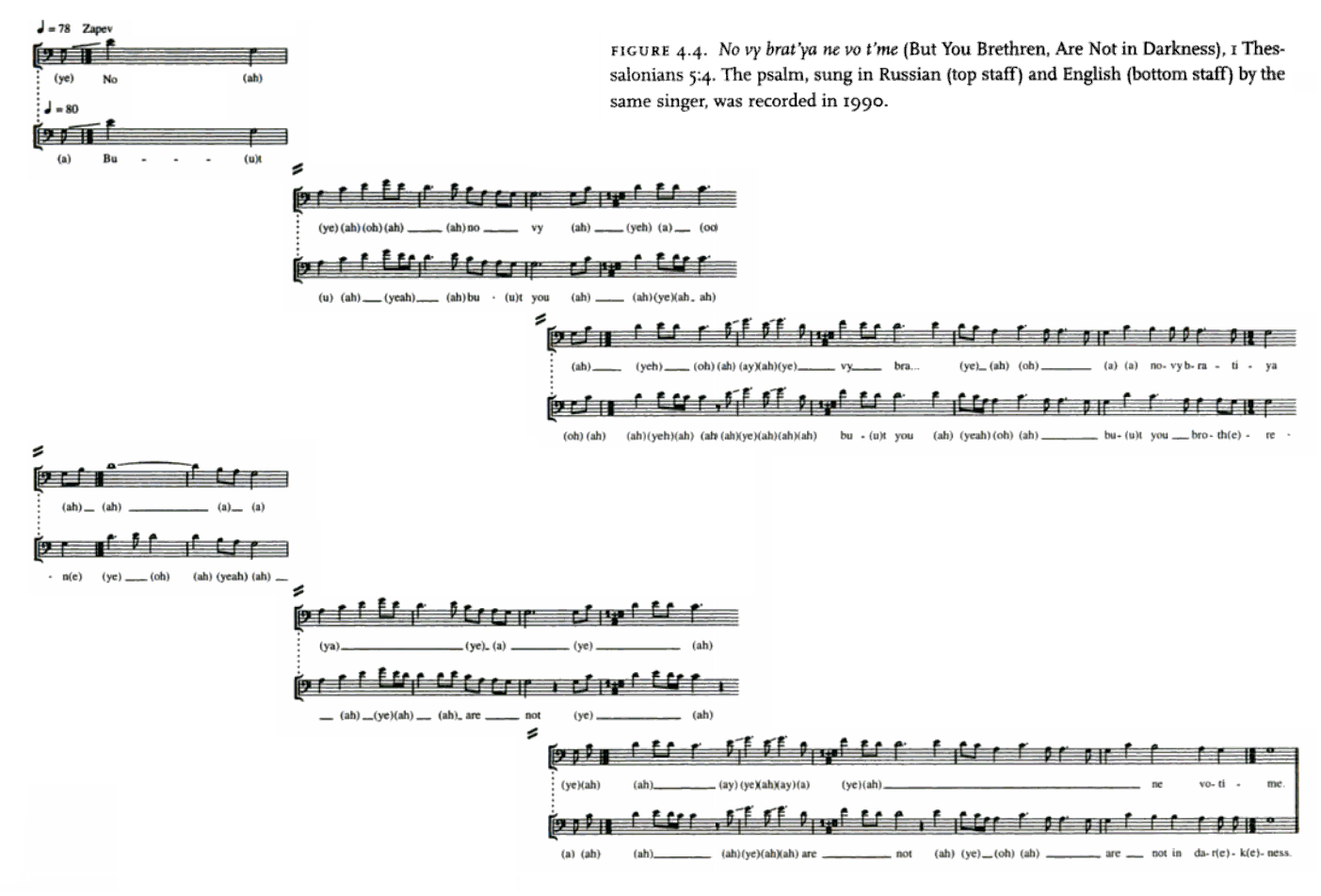

- Novy brat'ya ne vo

t'me (But You Brethren, Are Not in

Darkness), I Thessalonians 5:4. The psalm, sung in

Russian (top staff) and English (bottom staff) by

the same singer, was recorded in 1990.

Dukh-i-zhiznichestvo

Dukh-i-zhiznik

the Dukh-i-zhiznik faiths

Dukh-i-zhiznik faiths

Understanding why singing is so crucial for the perpetuation of the Dukh-i-zhiznik

Dukh-i-zhiznik faiths are

Needless to say, the collective experience and the experiences of the individual are completely interdependent, if not altogether inseparable. Anyone willing to approach a living culture as a dynamic, complex, and) dialectic phenomenon is confronted with this multidimensional dilemma. The dilemma emerges as he or she strives to integrate conceptual abstractions with specific individual experiences, to address the Bakhtinian “self/other” relationship, and to articulate deeply interdependent cognitive views, social constructions, and cultural notions. During field research in various Dukh-i-zhiznik

One of the Dukh-i-zhiznik

Dukh-i-zhizniki

1. By Way of Historical Introduction

Dukh-i-zhizniki

Like the Dukhobors (spirit wrestlers fighters), a sect from which the Molokans branched out, the Molokans sought religious freedom from the Russian Orthodox Church and economic independence from state-imposed poverty through establishing a self-governing and egalitarian brotherhood. To this day, communal energy is considered to have more spiritual power than the spiritual energy of any individual.

Because of their resentment toward the Orthodox Church, the Molokans [and later Jumpers], like other Russian sectarians, were outlawed by mainstream society and were severely repressed throughout their history in Russia, where the autocracy and the Orthodox Church were inseparable. In 1805, Molokans submitted a written petition to Czar Alexander I, and three Molokan spokesmen were called to present their case in front of the Czar and twelve senators. They explained their beliefs, described the hardships that they had been subjected to for their faith, and begged for the Czar's protection.(8) A large group of Molokans from central Russia was soon resettled, on the Czar's order, in the area along the river Molochnyi Vody near Crimea, in the Tavricheskaya province, where a large Dukhobor settlement had already existed since 1801 (Livanov 1872, 2:95-8) [Map]. The Molokans were conscientious objectors. During the 1830s, they accepted Czar Nicolas I's offer to receive a fifty-year exemption from mandatory military service in exchange for their relocation from central and southern Russia to the Russian Empire's new frontier in the Caucasus mountains and Transcaucasia (Moore 1973, 19; Izmail-Zade 1983, 55 [Breyfogle]). After the law allowing exemption from military services expired, their further petitions to be excused were denied. In conjunction with the millenarian prophecies of impending doom, many Molokans [and Jumpers] migrated further south and east to central Asia and Siberia. By the turn of the century, a large number of [Jumpers] Molokans, led by the prophesies, had settled beyond Russia's borders, in Turkey, Persia, Germany, Australia, and other parts of the world (see Livanov 1872; Klibanov 1982; Moore 1973; Izmail-Zade 1983). In the United States the first [Jumper] Molokan settlers arrived in the Los Angeles area in 1904-05.(9)

There are currently three main Molokan groups both in Russia and in the United Stales: Postoyannye (Steadfast), who claim not to have changed the original doctrine and order of worship; Pryguny (Jumpers), who, under a condition of communal ecstasy and mystic solidarity, seek a direct manifestation of the Spirit, whose embodiment may come in jumping, prophesying. and speaking in tongues; Maximisty*, who branched out from the Jumpers and revere the teachings of the late nineteenth-century prophet Maxim Rudometkin as much as they revere the Bible. A new branch** of Molokanism, currently emerging in me United States, is a group of Reform Molokans, who has yet to be mentioned in the literature. I have worked with all four groups, although my experience with the Maximisty has been limited, particularly in the U.S., as they are almost entirely closed to outsiders. Each group refuses to yield regarding separatism and independence. The differences among them are marked by a wide variety of issues, ranging from doctrines, liturgical practices, and ways of interacting with the outside world to family relationships. Internal disagreements further caused the three main groups to split into smaller units, each believing it strictly follows "the form prescribed by the founders of our denomination" (Berokoff 1987, 195). In reality, forms of practicing Molokanism [and Jumpers] are numerous and vary from church to church and even from individual to individual.***

[* Historically Maksimisty are a sub-group of Jumpers who use the Book of Sun: Spirit and Life for worship. See: “Holiday and Song Taxonomy of Molokans and Jumpers.”

** Reformed could also be classified as an English variety of Jumper, and not a "branch." See: "Holiday and Song Taxonomy of Molokans and Jumpers." Unfortunately Mazo uses the umbrella term Molokan for all of these various groups, which have evolved into different denominations, with different liturgy, though some ritual and song is common to all three faiths. This confuses the casual reader and recent scholars who have yet to uniformly differentiate these denominations.

*** Therese Muranaka was the first American historian to address this point. In her booklet "Spirit Jumpers: The Russian Molokans of Baja California" (San Diego Museum of Man, Ethnic Technology Notes No. 21, 1988) she quotes a line from S. Stepniak (The Russian peasantry: their agrarian condition, social life and religion, 1888, page 266): "Orthodox peasants were wont to say that among the Rascolniks 'every moujik (peasant man) formed a sect, and every baba (peasant woman) a persuasion'".

Extending the definition of Molokan beyond the Reformed, the 2002 hijackers of the Church of Spiritual Molokans of Arizona, founded as a Jumper congregation, who keep illegally changing the name to Church of Christian Molokans of Arizona, and call the police to arrest trespassers at the assembly and cemetery (3 arrests so far), falsely testify in court and to police (felonies) to be the real congregation. They have fooled the UMCA to list them in the UMCA Molokan Directory twice, 2004 and 2008. They have no relation to Jumpers or Molokans but the genealogy of their family or spouses, and the most aggressive (Mike Zaremba, Pete Uraine, Jack Conovaloff) are/were members of other faiths who were recruited to illegally take possession of the property by one family of delusional Tolmachoffs that knows nothing about performing Jumpers services, in English or Russian.

A different case arose in 1977 when a California man requested no photo on his driver's license for religious reasons. Denied, he researched court law and found the case of John Shubin, a Masksimist who got a photo deferment in 1980 claiming his "Molokan" faith prohibited photos. The man requested the same treatment claiming he was a also a Molokan in his own church, appealed and won in 1984. See: Jumper Exemption = No Photo on Driver's License? NOT!]

2. The Role of the Spiritual

The Dukh-i-zhiznik faiths are

Regardless of the religious and cultural integration that it manifests, the Dukh-i-zhiznik faiths are

Although Molokans [and Jumpers] seek a high quality for their earthly life, probably stemming from their effort to build an independent and self-sufficient spiritual community in preparation for Christ's kingdom on earth [mostly for the Jumper-S&L-users],(11) material symbols have little significance in their religious life. Like other Russian sectarians, Molokans [and Jumpers] completely abandoned the Russian Orthodox Church. They did so by rejecting all ecclesiastical hierarchy, rituals, the calendar of feasts and fasts, and all material attributes pertaining to Russian Orthodoxy, including, the most sacred of the sacred, the icon and the cross. They believed only in what they consider as internal spiritual aspects of Christianity, accepting only the symbolic essence of religious sacraments. Salvation accrues through faith alone, Molokans claim [original Molokans valued works and deeds], not in the church's ritualistic celebration of sacraments made as "objects of human artistry." "The Lord is the Spirit." and the ultimate enlightenment of "receiving the Spirit," the Molokans believe, comes through experiences unfathomable by the senses and logic (Dogmas, 12-3). It is not to be sought in the material world, but only in the spiritual world through communal worship "In spirit and truth." Such a notion of spiritual and communal power, which is the key issue in Molokan self-identity as a group, is nicely summed up by their original name, Spiritual Christians.

The functioning and perpetuation of Molokan spiritual life transpire entirely within the community, with the exception of using the Bible, that is, "God's word," as their major source of spiritual nourishment. For Molokans [and Jumpers], not unlike for fundamentalist Christians, the Bible has become not only the theological foundation of their beliefs, but also a lens through which they view, interpret, and gauge everyday life. Molokan interpretation of the Bible is largely associative and metaphoric rather than literal [but many S&L-users take it literally]. The Molokans use this approach to find in the Bible guidance for practically any need, from interpretations of doctrinal concepts to explanations of their name, song structure, or the most pragmatic daily activity. Interpretation through analogy and metaphor becomes a favorable rhetorical instrument in any Molokan [or Jumper] discourse.

3. Support System—Zakon [the law]

Molokans [and Jumpers], like many other confessional groups, have established a whole order of life to separate themselves from ne nashi. Living in a state of consciousness affected by their perpetual separation from mainstream society, whether in Russia or elsewhere, Molokans [and Jumpers] were forced to take charge of their own lives, both spiritual and physical, in an orderly way. As Young has pointed out, in seeking to provide individuals with "a secure refuge against doubts, uncertainties, and conflicts, which rage outside the sect," their communal life has become highly structured ([Young]1932, 273). They call this order of life "our zakon," literally, the law. In a more inclusive way, however, [Jumper] Molokan unwritten zakon refers to a distinct and self-sufficient maintenance system responsible for the stability and well-being of the community. Through a system of privileges and obligations, restrictions and prohibitions, this self-imposed zakon governs not only pragmatic matters, from behavioral codes to sociocultural institutions, but also spiritual issues, including values, worldviews, and the relationship between humanity and God. Molokan [and Jumpers] singing too is regulated by zakon.

Today, many young and middle-aged [Jumper-S&L-users] Molokans consider their zakon to be “too hard, too strict and too demanding.” Their struggle to live by the highest standards of zakon reveals the unbridgeable disparity between the realms of the doctrinal ideal and earthly necessities. At the same time, to fulfill its function as a guardian of Molokanism, zakon must be tolerant enough lo accommodate and reconcile the inconsistencies of individual needs and internal tensions. Thus, a continuous dialogue of competing interpretations is supported by zakon. As frequent and heated as [Jumper] Molokan debates over zakon are, they are essential venues for individuals to construct and negotiate its new meanings. Understanding the significance of [Jumper] Molokan commitment to verbal discourse is important for our purpose here, as it helps build a conceptual framework for understanding Molokan [and Jumpers] singing. In Molokan [and Jumpers] teachings, singing exists only in the unbreakable unity with slovo, the word. "Music could never be an art. It [is] a form of speech." according to one [Jumper-S&L-user] Molokan singer (James Samarin 1975, 65).

[Jumper-S&L-users have a characteristic of yielding to a majority of one. If one guy gets agitated and demands his way, he can dominate a meeting without opposition until the flock reluctantly follows. This is a fuzzy application of "the law" [zakon] — peer pressure interpreted as unwritten religious norm. The common result is a group not doing anything for fear of one person attacking. All must look and act alike — beards on men, fancy Russian peasant clothes, etc. Pundits say we left the Russian Orthodox Church due to its rules and rituals but came to America and created our own orthodox church with new rules and rituals. Abuse of zakon has divided many congregations. Western Jumper-S&L-users have less total Sunday worshipers but more congregations each decade for 50 years.]

4. The Role of the Verbal

While many closed communities are keen about self-reflection through words, the Molokans [and Jumpers] demonstrate an especially strong proclivity toward verbal expression. In aspiring to give their inner life a rational order, they devote great effort to constructing their ideas and experiences through verbal language. Molokan [and Jumper] verbal discourse is dynamic, not reducible to specific categories and forms. Instead, it has generated a web of rhetorical situations corresponding to various occasions and contexts, including communal worship, training sessions, and private discussions. In this light, it is not by chance that Molokans [and Jumpers] have a strong tradition and history of practicing rhetorical discourse. They greatly appreciate the ability to articulate and develop one's thoughts in an orderly fashion and consider it a special gift from God. To utilize this gift fully, and motivated by the utmost respect for the written text. the community has produced a profusion of books containing creed, prayers, and songs through which they have systematized and rationalized their thoughts and beliefs.(12) Some Molokans [and Jumpers] have even published their personal discourses on spiritual matters individually. It is significant, in the context of our discussion, that the very first publication of dogmas had a chapter "On singing." and the first publication of The Molokan Prayer Book included a list of psalms to be sung at every communal function and ritual. [Each denomination has their own prayerbook, with versions.]

The distinct expressions and terms of Molokan [and Jumper] verbal discourse are adopted from colloquial Russian language. Through metaphoric use these casual expressions and words have been either modified or refined in such ways that their connotations can no longer be easily articulated, but instead bear unique symbolic meanings. In a sense, they have become semiotic symbols. One does not have to search hard for these symbols of concepts and experiences that the Molokans [and Jumpers] themselves have singled out to denote their cognitive universe. It is enough to listen to the American Molokans [and Jumpers] who do not understand Russian. For the sake of preserving the symbolic meanings of these Russian expressions and terms, they use them without translation.

5. The Communal Worship and "Church Jobs"

Sobranie,

translated here as “communal worship,” literally means

assembly of people.(13) The structure

and communal nature of Molokan [and Jumpers] sobranie determines

the ways in which singing is conducted. The service is

guided by [volunteer, unpaid] prestol,(14) a

relatively large leadership group of experts. This is an

all-male group of which each person is chosen by the

Spirit or on the basis of his gift from God to carry out a

particular function during sobranie, that is, a specific "church

job." Church jobs manifest an order, based on a

recognition of different gifts from God. The church jobs

are the presviter (presbyter,

minister),

besednik (a

discussant, commentator and interpreter), pevets (a singer), skazatel' (here, a

reader or an announcer who prompts the psalm's text to a

singer), and prophet. Only singers and prophets can be

both men and women, but even if recognized for their gift

from God, the women are not part of the prestol and sit

separately (see fig. 4.1) [In congregations lacking men (like in Rostov

oblast), the women are prestol. The role of besednik has been

performed by outspoken women in the US (Big Church,

Arizona) and Russia (Piatigorsk). In some Russian Jumper

congregations (Piatigorsk), the woman prophetess also

sits at the table.]

Sobranie,

translated here as “communal worship,” literally means

assembly of people.(13) The structure

and communal nature of Molokan [and Jumpers] sobranie determines

the ways in which singing is conducted. The service is

guided by [volunteer, unpaid] prestol,(14) a

relatively large leadership group of experts. This is an

all-male group of which each person is chosen by the

Spirit or on the basis of his gift from God to carry out a

particular function during sobranie, that is, a specific "church

job." Church jobs manifest an order, based on a

recognition of different gifts from God. The church jobs

are the presviter (presbyter,

minister),

besednik (a

discussant, commentator and interpreter), pevets (a singer), skazatel' (here, a

reader or an announcer who prompts the psalm's text to a

singer), and prophet. Only singers and prophets can be

both men and women, but even if recognized for their gift

from God, the women are not part of the prestol and sit

separately (see fig. 4.1) [In congregations lacking men (like in Rostov

oblast), the women are prestol. The role of besednik has been

performed by outspoken women in the US (Big Church,

Arizona) and Russia (Piatigorsk). In some Russian Jumper

congregations (Piatigorsk), the woman prophetess also

sits at the table.]Figure 4.1. Molokan Sobranie seating

arrangement.

Although all church jobs are necessary for conducting a proper service, their makeup is elaborately hierarchical, and the hierarchy is maintained rather strictly [in large established congregations. Small congregations, particularly Jumper-S&L-users are flexible with roles.]. Church jobs also define the ways in which singing reflects the social fabric of the community. Each church job, [usually] with the exception of the prophets [only among Jumpers], is overseen by a starshiy (the head person), whose seniority in the hierarchy can be irrespective of age. A further ranking within each church job is based on various factors, including age, knowledge, skills, memory, wisdom, personal predisposition or God's gift, professional training, and revnost' (literally "jealousy," but in Molokan [and Jumper] use means eagerness to acquire the expertise and to perfect the skills for the job). [Political power of a clan or elder to appoint positions to relatives occurs and typically results in schisms, mostly among the Jumper-S&L-users.]

The structure and communal nature of the Molokan [and Jumper] sobranie in part determines the social make up of the community, and the church job hierarchy largely defines an individual's social status. Each job is a lifetime commitment and requires special expertise. Transmission of professional knowledge and skills is secured by formalized educational institutions and teaching processes specific to each church job. The job of pevets is considered one of the most difficult and requires many years of training.(15)

Holders of the jobs are all volunteers; Molokans [and Jumpers] seek direct contact with God in such a way that they reject the idea of intercession by paid clergy. Each person is expected to contribute [voluntarily, without pay] to the spiritual life of the community by contributing his own energy, thus helping build the communal spiritual power during sobranie. There are also not paid musicians. Musical instruments are not allowed, for they are considered objects of human artifice.(16) As far as singing is concerned, sobranie comprises only a cappella choral psalms and spiritual songs.(17)

“The order of service is simple,” notes Pauline Young when describing the sobranie (Young] 1932, 32).(18) Indeed, sobranie does not contain any elaborate liturgical acts. Stripped of the effects of bright and solemn costumes, icons and frescoes, lighting and incense, [Jumper] Molokan sobranie takes place between bare white walls with backless wooden benches. The only props are religious books on lop of a plain rectangular table covered with white cloth. In rejecting all visual attributes of Orthodox religious service, however, sobranie has given different aural forms of verbal and non-verbal communication crucial roles in channeling spiritual energy among the worshiping community. As a result, even if the service order of sobranie is considered "simple," the ways in which its sonic aspects are pursued and managed are immensely intricate. The sobranie's sonic aspects, once the dynamic relationships of all aural forms are considered, tellingly reflect rational order in Molokan [Jumper] spirituality. [Jumpers singing was much more original in 1919 when Young did her work.]

Traditionally, sobranie consists of two parts. The first part [sitting] includes several repetitions of a cycle consisting of a beseda (literally, a talk or a dialogue; but here a discourse, a special rhetorical situation and a kind of" sermon by a besednik) and singing a posalom (old-Russian for psalm, both versions of the word are in current use), that is, singing a scriptural passage from the Russian version of the Bible, corresponding with [the Douay Bible], but not identical to the King James Version. The cycle begins as the presviter who leads the service signals to the starshiy besednik to choose a besednik for the first beseda. The besednik's task is to select and read a biblical passage and then interpret it in the light of the community's current concerns, using his specific gift and stalls of discourse.(19) There follows the singing of a psalm. The process involves intricate interaction within the hierarchy of the entire prestol and the congregation. In brief, the singing can begin only after the presviter has given a signal to the starshiy pevets. The latter, in turn, assigns one of the pevtsy to select and lead a psalm. The selected pevets then becomes the main figure in the singing of this psalm. Meanwhile, the starshiy skazatel' assigns a skazatet', whose responsibility is to recognize instantaneously the psalm, promptly find the text in the Bible, and call out a short passage that will be fitted to the melody by the pevets.

How melodic is the prompting of the skazatel' depends on the local school and personal talent, but his intoning must never disturb the mood of singing. The visual contact between pevets and the skazatel' is secured by the seating order; they are located across the prestol (see fig. 4.1). The job of skazatel' is to work in perfect coordination with the pevets, timing the reading and choosing the length of the prosaic text exactly as the particular pevets requires. If the pevets does not know the biblical passage from memory, a smooth performance largely depends on the skazatel's skills. Note that an important characteristic of an experienced pevets is his ability to line up the words to the melody in a meaningful manner, so that the congregation can follow him. As the assigned pevets sings, other pevtsy support him, building the multivoice texture, appropriate for the local style.(20) The entire congregation participates in heterophonic singing za sledom (literally, "following one's footprints," here to follow the pevets). Then the beseda-psalm cycle repeats as many times as the presviter requires.

Ideally, the entire sobranie is unified by a theme, "the golden thread,"* to use a Molokan [and Jumper] expression, that runs throughout the service. The interpretive commentary on a biblical passage read by a besednik does not stop with the end of his beseda. It continues in the succeeding singing of a [related or supporting] psalm. The job of the pevets, thus, is not only to lead the singing per se but also to respond to the beseda and select an appropriate psalm instantaneously. Specific religious holidays or specific secular occasions certainly call for particular topics of the beseda and for particular psalms, but in a regular Sunday sobranie, the choice of the topic depends, to a large degree, on the first besednik.** Sustaining the golden thread* thus depends on the cooperation of all members of the prestol and their continuous concentration throughout sobranie, as they do not know in advance who is going to be called to officiate the next component of the service. Clearly, all church jobs require special expertise: all jobholders must be extremely knowledgeable of the scriptural text and have proficient skills in their particular duty. That is to say that the hierarchical nature of the "church jobs," while seemingly incongruent with an egalitarian community, is in fact indicative of a community that reveres order and also values equally the use of specific gifts from God to maintain order.

[* Knowledge and use of the “golden thread” has been lost among American Molokans and Jumpers, mainly because it requires Russian literacy and broad knowledge of the Bible and songs.

** Many congregations start with a psalm, which starts the "golden thread". Sometimes Jumpers start the thread by a reading a random selection of verse, a form of Bibliomancy called okreveie, literally "revelation".]

The climax of the sobranie falls in the second part [standing], which consists mainly of the communal prayer proper, formed by the combination of various prayers. Before the second part begins, all the benches in the service space are quickly removed. The congregants stand throughout this part of the service. Thus, in contrast to the first part, where the presviters, besedniki, skazateli, pevtsy, prophets, male congregants, and, separately, female congregants all occupy well defined spaces, the communal prayer proper has all the congregants gathered in a conceptually and physically different space.* Through their movement into this space, it is as if all the petitioners in the prayer were stripped of their professional and social positions to form a united body before God.(21)

[* Not really. They stand in approximately the same formation as they sat with the same jobs and roles depending on how much room they have to spread out. Often in Russia, in large congregations with resettlers from different geographic regions who can sing in the same style, a choir will temporarily stand together, sometimes men and women face to face, for their psalm, which other congregants will not know. At the end of their psalm, they will try to return to their previous standing location. Mazo was not able to attend many prayer services.]

Public, communal prayers offered either by a presviter, or by a presviter assigned individual [Russia: zamestitel', deputy presbyter; America: pomoshnik, helper], must be perfectly memorized and recited so that everyone is able to hear him clearly. In contrast, other members of the congregation intone their individual prayers privately and spontaneously (the sonic form of the communal prayer will be discussed later). Concluding the sobranie is a symbolic communion ceremony accompanied by singing.(22) Subsequently, one more short prayer is recited and one more psalm or song is sung for the closure of the sobranie, traditionally forming the end of the Steadfast [Molokan] service [which probably started at 8 am and ended at noon]. At the end, several additional spiritual songs may be sung; these can be started by women [usually selected by the head singer]. In the Jumper churches, "spiritual jumping," under the influence of the Spirit, often occurs at this moment, although deistvie (acting in the Spirit manifested by raised hands [often one hand in Russia, always two hands in America and Australia], stomping feet, or other bodily gestures) may have occurred at any moment earlier. Prophecies may also take place at any time, with utterances in a tense and harsh voice as well as speaking in tongues.(23) [Glossolalia, "speaking in tongues", is nearly lost among Molokans and Jumpers in the U.S. and Australia. Among Molokans perhaps because they rarely elevate emotions during worship. Among Jumper-S&L-users perhaps because it is perceived as out of style, and/or from the 666 false faiths warned about in the S&L. Ironically, Dr. William J,. Samarin (brother to James and Edward) was a pioneer in glossolalia research.]

It should be clear from the above description that sobranie unfolds both “by the Spirit and by the mind." While spontaneity and flexibility of the choices made by the experts play an important role. the sobranie relies on the professional knowledge and skills of the experts, who work in dynamic relationships within the overall design predetermined by the zakon.(24) Ordinarily, as far as I have been able to observe, any deviation from this general structure occurs only under special circumstances and as an exception that needs to be justified and negotiated. The construction of negotiated meaning thus becomes an important instrument for introducing necessary transformations or deviations from this order, specifically at the moments when certain individuals or the entire community undergo some drastic changes or stress. [Notably, sobranie has shortened from 4 hours to 1 hour for some small Jumper-S&L-user congregations in the U.S. Services vary among congregations, who often split due to differences in ritual.]

6. The Power of Singing

The sobranie involves different aural forms or sound modalities:(25) speaking, reading, sermonizing, praying, singing, and [for Jumpers] prophesying. Each sound modality has a distinct paralinguistic profile marked by specific tempo, volume, intensity, timbre, pitch contour, and duration. For Molokans [and Jumpers], all aural forms used in sobranie are based on the Scripture, God's word. And "God's word is made of sound," teaches one of the spiritual leaders of the [Jumper-S&L-user] Fresno community. Yet the symbolic power of the different forms of God's word is not the same. It seems that for Molokans [and Jumpers], the power of God's word consists not only in the meanings or contents of the word, but also in the sound modalities through which it is delivered. Of all the modalities on the sound continuum of sobranie, singing is attributed with a particularly great power. God's word, when sung, occupies a remarkably high point in the service in the eyes of the congregants.

Many religious communities recognize the enormous symbolic power of singing in engendering collective experience. Some of them in fact privilege participation in the communal act of singing so much that they seem to show little concern for the technical and expressive quality of the actual singing. It is not so for the Molokans [and Jumpers], for whom singing can either stifle or vitalize the sobranie, and "good" singing is crucial. They even have the concept of "a quality singer." although its precise definition is not easy to construct. "Singing brings man to Cod." many [Jumpers] Molokans say, and a "poor" performance during the sobranie might prevent the congregants from reaching a spiritual state where they could communicate directly with God.

Singing as a source of spiritual power is a common discourse among the [Jumpers] Molokans: "Singing is to melt the heart, and then your heart opens itself to God's word. Singing reveals the word of God to man." In their universe, singing thus is not only inseparably bound to God's word, but also has the power to make the work of the Spirit tangible and directly accessible for people. The connection of singing and spiritual energy is not simply an abstract theological notion written down in the creed and used in rhetorical situations; it is a very actual and personal experience, one of the most valuable experiences of [Jumper] Molokan worship today. A number of skilled [Jumper] leaders say that it is singing, more than anything else. in which they engage during the sobranie, in order to communicate with the divine. In the act of communicating with the divine, singing is indispensable:

First, the [Jumper] singers

start singing, and this will bring us the spirit, but not before the singers

start singing. God says: "If you want me to

tell you something, call the singers, and then I will

speak the word to you." We sing to praise God, and if He

wants to announce something to us. He will do this

through our singing"(emphasis added).

It appears that in the context of the [Jumper] sobranie, "God's word" is understood as a metaphor for the "presence of the Holy Spirit." Liturgical singing is the primary instrument in building up the presence.(26) Thus, sanctity does not reside in the psalms and spiritual songs as such, but rather in the instance when the psalms and songs are sung.(27)

Undoubtedly, singing is an act of the divine for Molokans, whose image of heaven is impregnated with singing: "All those who have earned their access to heaven sing. There [in heaven], they do not work, either do they eat; they only sing." Yet while Molokan singing is a divine act, not least because it channels the work of the Spirit in guiding the selection of psalms and songs in the sobranie, it is at the same time a rational act. There is abundant evidence that Molokans [and Jumpers] sing as much "by the mind" as "by the spirit" First of all, many Molokan [and Jumper] psalms are highly complex, demanding sophisticated musical skills; they are also impossible for the congregation to sing without the competent leadership of the pevtsy. Second, the rationality of Molokan [and Jumper] singing is manifested in the thematization of their psalms. A number of Molokan psalms are occasion-specific. These psalms arc divided into various categories on the basis of their message. There are psalms to console, to beseech, and to give thanks; there are also psalms for funerals, weddings, birthdays, and house warming. Out of more than a thousand psalms in the community's collective memory, however, only a few* share a common theme to make them suitable for the same occasion. In choosing a psalm, it is necessary to match the psalm's message with the golden thread of the sobranie. Choosing a psalm proper for an occasion is of great importance; it is a task left to the pevtsy — the ones with the greatest gift in this area of expertise among the community.

[*Some occasions have many possible psalms, depending on the skills of the singers.]

All its unique Molokan [and Jumper] features notwithstanding, the sonic in the sobranie has a function shared by the sonic in similar ritualized contexts in other cultures: to induce a truly communal experience among the congregants. In the words of one [Jumper] Molokan, "[Through] singing, the Spirit comes to other people [. . ] so everyone will be united." This function also produces a coalescence of the emotional and the rational, a process dearly manifested in the performance of the skillful pevtsy. In singing during sobranie, the pevtsy have to be fully in control — appropriately detached — at all times in their response to various ritualized situations, without becoming too excited or involved (Mazo 1990, 119-20). Arguably, it is precisely the sense of communal unity created through synergetic states of many different individuals during singing that contributes to the emotional intensity and potency of the worship.

7. Transformations of Singing during Sobranie

The communal worship styles of the Steadfast and Jumpers are not exactly the same. Accordingly, their singing also differs in certain ways. If both psalms and spiritual songs are essential for the Jumpers, the Steadfast Molokans allow songs in worship only after the sobranie proper has ended, if there is any singing at all. [Essentially Steadfast Molokans and Jumpers are different denominations, not varieties of one denomination.]

During the sobranie of the Jumpers, when physical manifestations of God's blessing are sought, appropriate singing helps the participants achieve a religious trance-like state they call deistvouat' (literally, "to act." but used by [Jumpers] Molokans in a sense of "being in the Spirit'). The works of the Spirit bring changes in the physical behavior of the individual congregants and induce the jumping that gives the group its name. Although prophetic ecstasy and deistvie, the definitive assurances of the community's spiritual vitality in the eyes of the Jumpers, can occur any time, they often commence during singing and cease as soon as singing stops. [Singing will continue if a Jumper seems to need it. Fast, loud singing and stomping are complementary.] Moreover, according to one [Jumper] Molokan singer, singing has always been used for the attainment of deistvie. This duality of spontaneity induced by divine inspiration and mediation controlled by one's professional singing skills is not perceived by the Jumpers as a contradiction: "Music has never been held in greater honor, nor cultivated with more judgment and high artistic sense, spiritually speaking, than at the time when a song properly sung arouses the prophet to ecstasy." For this singer, "To prophesy meant to sing, and there is little doubt that Isaiah, Jeremiah, and others uttered their prophecies in song" ([American Jumper-S&L-user] James Samarin 1975, 68 and 65).

An experienced observer can anticipate the approach of deistvie from changes in the singing. Musical patterns become more fixed, easier to recognize and predict, thereby drawing less attention to themselves; they are meant to pave and adorn the road toward taking part in the congregants' most significant trance-like experience. In my observations, the communal deistvie is not connected with what a musicologist would select as the most powerful laconic pattern repeated over and over with accelerating tempo, swelling volume, and growing intensity of sound. [Jumpers] Molokans call this type of singing udaritel'noe (from udarenie, "emphasis," or "accent"), a term that eludes precise definition but can be loosely rendered as percussive, accentuated, forceful, and emphatic. Unlike psalms at the beginning of sobranie, udantel'noe singing is syllabic, it is not smooth, but rather staccato-like, with frequent and forceful breathing.(28) The character of musical prosody also changes in udaritel'noe singing; the accentuation of every beat-syllable becomes more and more intense, thereby transforming the melody's metric pattern into a throbbing one-pulse meter. The speed and the rhythm of jumping, as far as I could observe, concur with the pulse of the song. "We want the Holy Spirit, that is why there is rhythm,“ says an elder woman, “jumping and rhythm are related.” I have never observed any significant deviation between the voices, either in melodic contour or rhythm. The participants breathe and sing as one, and their individual energies completely synchronize and become one synergetic whole.

The spiritual life of the Steadfast Molokans is less apparent to an observer, but here, too, singing intensifies during the service through increasing the voices' volume and intensity and gradually raising the pitch level. In both denominations, the climax of the service, the communal prayer, is a complex sonic whole: a prayer recited by the presviter sounds simultaneously with the personal prayers of all the others. These individual petitions to God blend into a single multivoice communal moaning, in which individual voices are hardly perceptible. Careful listening, however, reveals that most often the individual petitions are expressed in a form close to Russian village lament (dirge or keening), in which melodic recitation is mixed with tears and sobbing, sometimes even wailing.(29) As during other village rituals that use simultaneous laments (e.g., funerals and weddings), all participants employ the same melodic formula, although each renders it in an individual way. As with village laments, these individual prayers occupy the border of musical, paramusical, and paralinguistic expression. The application of laments during the communal prayer becomes conceivably more comprehensible if one keeps in mind that lamenting, not unlike such prayer, brings a cathartic feeling of relief.(30)

The instability of pitch in laments is one of the important indicators of the performer's emotional involvement. Similarly, in Molokan [and Jumper] psalms sung during the first part of sobranie, before the communal prayer, the pitch level is usually unstable and rises within each psalm.(31) After the communal prayer, of which the prayer-lament is a prominent component, the local pitch level becomes more stable, or even entirely stable. The particulars of the pitch level certainly vary from case to case, but I observed this general tendency during many Molokan [and Jumpers] services, both in Russia and the United States.(32) The process of “praying” or "petitioning,'' here often with lamenting, helps to bring out an outburst of extreme emotional intensity, and as a result, the state of catharsis is achieved. Thereafter, the pitch level becomes more stable.

During the first part of the ritual, [sitting] before the prayer, each sound modality is temporally well defined and can be isolated from the others in a sequence: reading followed by a discussion, pronouncing, and singing. Later, at the climactic moment of the service [standing], distinct sound modalities become compressed in the ritual's metaphorical time and space. This is to say that the boundaries between separate modalities become ephemeral as the sounds of the "public" prayer, singing, and private prayers-laments fuse into one sonic whole. It is worth repeating that we have already observed a consolidation of all the congregants in the physical space of the Molokan [and Jumper] sobranie as well.

8. Molokan [and Jumper] Psalms: Transmission, Formal Features, and Performance Practices

Molokan [and Jumper] oral history preserves many legends and stories about Molokan singing and singers. According to the legends, the early forefathers of the Molokans devoted great attention to seeking special forms of songs and approaches to singing As one legend goes, Semen Uklein, the preeminent founder of Molokanism, sent special messengers all around Russia and to Cossack villages to listen to local songs and collect good ideas for Molokan psalms.(33) Indeed. Molokan singing exhibits various kinds of subtle and obvious ties with folk song. Molokan singing of psalms, nonetheless, has evolved into completely unique forms.

The transmission of Molokan singing relies on a combination of oral and written forms. Words of psalms and songs are, as a rule, transmitted as written texts. Psalm texts themselves comprise actual printed scriptural passages. Texts of spiritual songs are usually written down as soon as they are composed (or [with Jumpers] given to the individual believer by the Spirit [, prophet]) and then distributed as written poems. The text of a spiritual song can be created (or given) with or without a melody, but the melodies of both psalms and songs are always transmitted orally. While songs are still being actively composed, only one small group of [Jumper-S&L-user] singers in the Stavropol' area in South Russia, as far as I know, "is working" on psalm melodies, that is, composing new melodies or adapting existing melodies for different scriptural texts.* The names of the creators of [Jumper] Molokan psalms and songs usually are not announced and are known only to a closed circle of people. Because the psalms and songs are both the source and the manifestation of the communal power, they are considered to be something belonging to the entire [closed] community [of Molokans or Jumpers]**.

[* Maksimists are more inspired to add a "new song" from the living Holy Spirit, and to deliver fresh revelations.

** Many Jumper S&L-users, especially Maksimists are adamant in keeping their religion a secret from the world, obeying Rudomiotkin's order to not show these words to non-believers. They often cite the Bible, do not "cast your pearls before swine."

Before addressing the way in which Molokan [and Jumper] psalms function within oral transmission, a brief examination of their salient musical characteristics is in order. In a 1911 study, Evgeniya Linyova(34) offered the earliest and still the most comprehensive published discussion of the general characteristics of Molokan psalms:

The singing is very broad

and melodious. Under the influence of the dignified,

flowing style arises a deep religious feeling, not

ascetic or gloomy, but gladsome, full of life. Very

remarkable is the form of the musical period. The text

of the psalms is not rhymed, and this necessitates a

very long musical period, quite as long as the

corresponding verse. The working-out of such broad

melody, which passes a complicated design of free-voice

pans, necessitates a very gradual crescendo and a

complete absorption of the singers in the musical and

ideal contents of the psalm. (Linyova

1911, 188-89)

Sung directly to nonrhymed scriptural passages, psalm melodies have to accommodate prose phrases of different lengths and accent patterns. This results in their exceptionally elaborate formal structures and asymmetrical phrases, some of which can be repeated as many times as the particular text passage requires.

Figure 4.2. Ya skazal pri polovni dnie moikh (I Said in the Cutting Off of My Days.) Isaiah 38:10, Comparison of A Russian and American versions of the psalm recorded in 1990. [Russian]

Figure 4.2 presents a comparison of two analytical transcriptions of the same psalm, sung by two Russian and two American lead pevtsy.(35) The visual alignment of the transcriptions reveals that regardless of all the differences, these are two versions of the same melody. The melody is "difficult." according to the singers. Indeed, the intricacy of this melody is not easy to grasp at once. Yet this makes their similarity striking, especially considering that the melodies have been orally transmitted separately thousands of miles apart for almost a century. In 1990, when I recorded both melodies, these Russian and American performers had never heard or seen each other; there had been no contacts between these two communities for many decades. This fact brings up an important and fascinating question of stability in oral transmission, though this discussion cannot be undertaken here.

The spatial layout of the transcriptions in figure 4.2, with the similar melodic gestures aligned vertically, also reveals how the melody as a whole evolves through repetition and subtle variation. The melodic building blocks, expanded or constricted in various ways, are almost never repeated exactly. The design of this melody is certainly very complex, but, like other psalms, it has its own specific logic, making the melody recognizable in various performances and in various local styles.

Many psalm

melodies, like the one in figure 4.2, show strong links

with protyazhnaya songs

(long-drawn-out),(36) the most elaborate

and melismatic form of Russian village song, even though

Molokan [and Jumper]

psalms are different in many respects (cf. Fig. 4.3).

Many psalm

melodies, like the one in figure 4.2, show strong links

with protyazhnaya songs

(long-drawn-out),(36) the most elaborate

and melismatic form of Russian village song, even though

Molokan [and Jumper]

psalms are different in many respects (cf. Fig. 4.3). Figure 4.3. Don Cossack protyazhnaya song transcribed by Alexander Listopadov in 1900 in a Don Cossack village Yermakovskaya (Listopadov, 1906, 214).

Like protyazhnaya, the psalm's melody is characterized by a periodic construction; both begin with a solo zapev (song's opening), a melodic gesture whose tonal content and overall shape determine the unfolding of the entire melody. Both are sung at a slow tempo, with the melody stretching out the text through extensive melismata. In both, the melisma is not a mere decoration; rather it is such an integral part of the melody that removing it will virtually destroy the melody's musical sense and unity. The syllables are not only lengthened, but also may be repeated, the vowels transformed, and particles and exclamations added, so that the sung text becomes almost incomprehensible. Yet contrary to what one might expect, when performed properly, the melismata. in spite of the various kinds of "interruptions," contribute to rather than disturb the song's artistic coherence. As in folk protyazhnaya, they endow the psalms with “a quality that fascinates by its freshness and power" (Lopatin 1956, 96). Protyazhnaya is known in many local styles. The style known in many local traditions in the South Russian and Cossack regions as singing with a podgolos, a solo upper voice with an elaborate melodic embellishment (see fig. 4.3), is particularly similar to a large group of Molokan [and Jumper] psalms.

[Protyazhnaya is not prominent among Molokans in Central Russia. It was apparently developed by sectarians, including Doukhobors, in South Russia (Ukraine) to camouflage their illegal religious services, rendering them not understandable by anyone who may hear. If a passerby could understand their non-Orthodox heresy, a misdemeanor crime could be charged. So protyazhanaya became a legal “loophole” to allow worship with singing.]

In spite of all the variations in performances, Molokan [and Jumper] pevtsy insist that many "difficult” psalms, as the one in figure 4.2, require extensive memorization: "You must learn the melody and sing it exactly the same, every time. You cannot cut something or add something, and if you do, you can easily turn the melody into a different psalm, lose it altogether, and confuse everybody." Many psalms are built from similar melodic gestures that are varied slightly or substantially and put together in different ways; it is indeed easy to see how one can "lose" a psalm. In addition, unlike in protyazhnaya, the text alignment in psalms is not fixed, but varies in each stanza and each performance, depending largely on communication between the pevets and the skazatel'. The melody has to be so familiar to the pevets that he may concentrate on fitting the prose in a sensible way, permitting other pevtsy and the congregants to follow him comfortably. [In America, sometimes Bibles are marked to show line cuts to be read. Top American singers claim they can start at least 300 psalms and verses.]

Accordingly, oral transmission of psalm melodies is more formalized than in folk song practices, with more conscientious memorization and less improvisation. This is not to say that improvisation is excluded from the performance of the psalms and every interpretation is "exactly the same" in the sense of written music. In comparison with Russian folk song, however, the boundaries of freedom in each performance appear to be closer to the regulations of written tradition and are confined to nonformal properties. Conforming to the rules of oral transmission, each singer has his own version of the melody, but my recordings of the same psalm by the same singers show an unusual degree of stability over a period of five years. The psalm transmission process, then, reflects how the overall Molokan [and Jumper] zakon perpetuates itself. If we take this parallel a step farther, one may argue that the liturgical performance of the psalms, with its hierarchical relationships between all participants and its intricate design, appears as a small-scale replica of the dynamic relationships between the components of the sobranie and Molokan [and Jumper] spiritual universe at large.

9. Comparison of American and Russian Singing

Molokans [and Jumpers], always conscious of their own history, are fascinated to hear the singing of their brothers living across the ocean. I asked American Molokan [and Jumper] singers to comment on psalms and songs recorded from their counterparts in Russia. In response, they often connect the differences in singing with differences in their life. Commenting on the singing of spiritual songs (not psalms), one prominent [Jumper] singer said, betraying his everyday life in Los Angeles through his reference to freeways:

We sing a song as we live

our life. We are rushing, and it is not right, because

the [Jumper]

Molokan singing is sad, sorrowful. In Russia we were in

need, and we sang sorrowfully. But we have everything

and don't need a thing. We jump on freeways, rush and

run for money. And this is how we sing.... We should

sing to melt the heart, but we sing to do the jumping.

Later, commenting specifically on a practice of singing psalms (not spiritual songs), he added:

They lessen the kolyshki [roughly,

"swaying"; a term of American [Jumpers] Molokans to indicate

melisma],

and

here we expand the kolyshki....

We

sing

like

our

costume,

lace

on

top

of

lace

on

top

of

lace,

with

a lot of kolyshki.

Comparing the singing of the same [Jumper] psalm by pevtsy from Russia and California in figure 4.2 may serve as a testimony to what he said. The American melody appears to be an extended version of the Russian one. The American version is slower and longer. It is even more melismatic, melodically elaborate and free ("lace on top of lace, with a lot of kotyshki”). Structural augmentation comes through large- and small-scale procedures, particularly salient in the addition of new melodic phrases at strategic points of the melody (see an elaborate melodic phrase as a new zapev by the California singers in figure 4.2).(37) The similarity between the American and Russian versions of a [Jumper] psalm is not always as self-evident as in figure 4.2. Many, however, are recognizable, particularly if a psalm has a unique melodic or rhythmic gesture (e.g., the octave leap downward before the cadential phrases in figure 4.2).

American pevtsy often comment on the voice quality of their Russian counterparts. Having a nice, "beautiful" timbre is not as crucial for Russian "quality pevets" while an American "quality pevets" must have "a good voice." It is not by chance that many [some] notable American Molokans [and Jumpers] have recordings of famous singers in their homes (Chaliapin. Lemeshev, Sobinov, Caruso, Lanza, Pavarotti). Neither is it accidental that American pevtsy who attended music classes in American public schools became interested in taking professional voice lessons in order to acquire some of the vocal techniques and vocabulary of classical musicians. This naturally has influenced both their manner of singing and vocal production, making them quite distant from the "folk manner" and "harsh voices" of traditional pevtsy in Russian villages.

[Mazo interviewed the most skilled and open to ne nashi singers, those most likely to study voice and music. But she did not interview many of the majority of young Jumper-S&L-users in America who shout instead of sing. This shouting style could be a transfer of loud rock, and punk music from the culture into sobranie. The few older singers schooled by the immigrant singers have practically no control over the young and often do not sing with shouters. Several quality singers have split to form family congregations, due to the incivility of shout singing and younger prestol.]

10. Keeping Russian Melody versus Russian Language

If we compare the way Russian and American singers handle the verbal text, we find a picture somewhat different from their handling of melody. While lining up the words to the melody after the skazatel'. Russian pevtsy exhibit more freedom. They may change some words, omit or modify others, repeat some syllables, and finish the melodic stanza not necessarily at the same point as the skazatel'. American pevtsy approach the text with more restraint than their Russian brothers. This is understandable, since for many singers Russian is no longer the language they know best.

For third-generation American Molokans [and Jumpers], Russian has become only the language of the ritual, like Latin or Hebrew in other liturgies. Young people do not understand it and cannot participate fully in the service. Still, until recently, maintaining the Russian language, at least as the language of religious rites, and, on a broader scope, of Russian culture, was an untouchable and a highly sensitive issue. Conducting sobranie, at least partially, in Russian has been perceived as part of the Molokan [and Jumper] zakon itself, and while English has been acceptable for beseda in some churches, prayers and psalms must be in Russian.

[Humor: God only listens in Russian. Russian persists in America as the liturgical or sacred language because (a) up to the 1940s the immigrant elders insisted that all will return to Russia*; and (b) it is related to the persistence of Old Church Slavonic. Old Slavonic is preserved among Old Believers and one Molokan congregation because it is the "language of God". Some Old Slavonic words are preserved among the prayers and verses, particularly among the American Jumpers-S&L-users who do not know modern Russian.

* In 1908, Berokoff reported the purchase of a cemetery in Los Angeles was not needed because elders wanted to leave the city, they were soon returning to Russia.

In 1918, Sokoloff reported they were soon returning to Russia. In the 1

John K. Berokoff says he was told not to bother translating the Book of Sun: Spirit and Life because we are soon going back to Russia. He only began punishing after it was obvious that no one was returning to Russian from California.]

Today, many among the third- and fourth-generation American Molokans [and Jumper] identify themselves as Russians, even though disparity between the two cultures is sharply sensed: “The Russian mind is different from the American one." Moreover, for the majority of American Molokans [and Jumper], the Russian language is thought to be an essential component of doctrine itself. Russian Baptists, Pentecostals, and Adventists living in the United States convert their service into English much more easily, and the loss of the language does not necessarily cause the weakening of their self-identity. For the [American Jumpers] Molokans, keeping the Russian language is apparently so crucial that they refuse to compromise even in the face of serious consequence: A number of younger people who do not understand the service and are not able to follow it gradually distance themselves from the church. The issue of the interrelations between religious, ethnic, and cultural matters is much debated in the community, and the opinions vary even within one family. [About 90% have left the American Jumper faith due to language, intermarriage, and interpretations of Christianity.]

Among several strategies that the American [Jumper] Molokans have adopted, one is very radical and deserves mention, especially because it has never been recorded in the [scientific] literature as far as I know. A small group of [5] young [Jumper-S&L-user] families in Oregon, who call themselves a Reform Molokan Church, following the path of other religious groups in United Stales, changed the language of the entire sobranie into English. The Oregon group is fighting in their own way to keep memory and culture alive, trading the language for the spiritual survival of [Jumper] Molokanism. The rhetoric about the significance of Russian is quite different in this church. For its members, the inseparability of ethnic, cultural, and religious matters is no longer an issue:

Some people think [Jumper] Molokan

is a nation; it is not. If you are a [Jumper]

Molokan, you're only a [Jumper] Molokan because of the religion.

[If] you join into this religion, into this church, then

you are a [Jumper]

Molokan. It is not a certain kind of a people or a

certain race of people. You could be a [Jumper]

Molokan. To be a [Jumper]

Molokan you, first of all, have to receive Jesus Christ.

That makes you a Christian. To be a [Jumper] Molokan, when you

join our church, you agree to abide by the by-laws. Then

you are a [Jumper]

Molokan.

Negotiating and redefining the meaning of some fundamental concepts of [Jumper] Molokanism by the members of the Reform church is presently very much in progress. The rhetorical discourse of the young leaders of this church promotes flexibility, an inclusive and accommodating approach that allows people with very different backgrounds to feel comfortable, thus manifesting an important departure from traditional rhetoric of the ne nashi. It may be too early to reach definitive conclusions, but as far as I know, conducting the entire sobranie only in English has been rigorously followed. During our conversations, the leaders would use Russian words freely — particularly those related to spiritual and religious matters: Presviter, pevets, skazatel', beseda, byl' v dukhe, and so on — just like American [Jumper] Molokans in all other churches. In the format setting of sobranie, however, even these have been translated as a matter of principle.

Singing is no exception: Psalms and songs are sung in English. At the same time, remarkably, Reform [Jumper] Molokans use only Russian melodies. Converting the sung portions of the [Jumper] Molokan service into English requires that they solve some technical difficulties. The strategies chosen for songs and psalms have been different. The lead singers say that the conversion of psalms to English, contrary to what one would expect, has been a relatively easy matter. Figure 4.4 illustrates this process by overlapping transcriptions of the same melody sung by the same singer of this church in Russian and English.(38)

In the English version, neither the structure of the melody nor the melodic details are changed. The singers do subject the English text to some of the procedures borrowed directly from a characteristic treatment of the text in Russian psalms. One can identify at least three such procedures. First, they extend certain syllables with long melismata. Second, they add vowels or semivowels into clusters of consonants, like "bre-th(e)-ren(e)" or "da-r(e)-k(e)-ness," even if this makes the English words sound quite awkward. Third, they inserted non-lexical syllables — "yo," "ya," "ah," "oh," and so on — into the text. Lining up these additional syllables with the melody and distributing the entire text over the melody coincide strikingly with the Russian version, in spite of the differences of structure or meaning in the English language. As a result, if there were a notion of a musical accent, their English singing can be said to have a strong Russian accent.

Figure 4.4. No vy, brat'ya ne vo t'me (But You Brethren, Are Not in Darkness), I Thessalonians 5:4. The psalm, sung in Russian (top staff) and English (bottom staff) by the same singer, was recorded in 1990. [Russian]

Handling songs has been more difficult. At the beginning, the Reform [Jumper] Molokans decided to keep the melodies unchanged and to manipulate the text to fit them:

I think that when I adapt

a song [from Russian into English] I do it so that the

English words fit the melody. That's the primary

concern. I retain the biblical thought, so that I don't

deviate from that. ... When I adapt a song, I just make

it (the English text) fit the tune that has been already

established.

A year later, the same singer came to distinguish the process of "adaptation" from that of "translation:"

My preference is no longer

to take a set of words and adapt them to the established

tunes. My preference from now on is to translate the

words exactly. . . . But if I come up with new words, I

am also to come up with a new tune as well.

The very existence of the group of [Jumper] Molokans who take issue of translation into English to such extremes has generated immense friction in the [American Jumper-S&L-user] community, deepening their separatism even further. Often, the members of the Reform church are shunned even by their [Jumper-S&L-user] parents, who believe that converting the sung texts to English causes their children to cease being [Jumper-S&L-user] Molokans. In the early 1990s, when I first visited the Reform group, there were only a few members, certainly not enough to declare the church to be officially functioning. Less than a year later, there were about thirty-five people during a regular Sunday service, and they have officially registered the church.

11. Resettling the Culture

Regardless of their different histories and living conditions during the twentieth century, Molokans [and Jumpers] in both Russia and the United States arc undergoing a similar spiritual development. In both countries, they make a serious effort to preserve Molokanism [and Jumper] and keep the younger generations within the tradition. In both countries, albeit in rather contrasting ways, Molokans [and Jumpers] feel threatened by the dynamics of contemporary life. If in Russia and the USSR Molokanism [and Jumper] had to withstand religious and ideological repression, in the USA the pressure comes, above all, from the gradual loss of language and new economic and cultural orientations.

Continuity of living space is often considered an issue of cultural conservation. For any culture, migration — change of living space — is like uprooting a plant into a different soil. But for several Russian confessional groups (Old Believers, Dukhobors [Doukhobors], and Baptists), living in Diaspora has also been a factor that has stimulated the preservation of culture, no matter where the groups settle. Throughout their numerous migrations over the last two centuries, Molokans [and Jumper] have thus far been able to negotiate a balance between preserving the old and creating the new. [Jumper] Molokans welcome an opportunity to borrow a melody and make any tune they like into their own song to praise God, at either religious gatherings or social occasions. Hit songs of all kinds, including songs from Soviet films and popular American songs, have landed in their repertory: "Amazing Grace." "It's the Last Rose of Summer," "Clementine," and "Red River Valley," just as “Korobochka.” "Kogda b imel zlatye gory,” and “Na zakate khodit paren''' have provided melodies for favorite spiritual [Jumper] songs. Émigré culture is often characterized as operating between two poles: memory on the one side and adaptation on the other. Among Molokans [and Jumpers] it is usually singing that fills in the continuum: A traditional psalm melody ensures continuity with the past,while composing and learning new songs link the past with the present.

Any small cultural enclave is unique, and often a single factor can change its practices drastically. A critical mass of people and the sufficiency of their singing repertory, for example, may be crucial for the survival of the Reform [Jumper] Molokan group. Most recently, one major change has affected the American Molokan community at large. As a result of new politics in Russia, the Americans were able to reestablish connections with their historical brethren. Singing together is always a high point of their meetings, and a cassette with recorded psalms and songs is one of the most precious gifts.

Molokans [and Jumpers] and village communities in Russia, no doubt, share many historical links. Many outer signs may serve as an example: An American [Jumper] Molokan man who wears a specially tailored shirt with a rope-like belt (granted, made from silk threads); a woman whose head must be always covered with a shawl (granted, made from lace); or one who speaks in a distinctly rural South Russian dialect and keeps in the closet a handwritten notebook with charms, almost identical with charms circulating all over rural Russia (granted, written down in Latin characters). Perhaps even more important, the spiritual life of Russian peasants prior to World War II, unlike that of the city-dwellers, was not a separate sphere of their daily life. Faith for these peasants was a way of living, permeating every aspect of daily life. Molokans, through their understanding of religion as a syncretic entity with no compartmentalization between life and faith, are closely tied to other peasant communities in Russia. The modem world leaves less and less space to such non-compartmentalized living for Russian Molokans [and Jumpers], and even less so for their American brothers and sisters.

The Molokans [and Jumpers], however, have always been distinct from other peasant communities in Russia. There is evidence that many Russian peasants had a rather limited knowledge about Christianity as a religious doctrine and often were not particularly interested in learning this side of religion (Mazo, 1991). The icons and dukhovnye stikhi (spiritual verses, songs with religious subjects sung outside the church) were often the peasants' most typical sources for knowledge of Christian creed.(39) In contrast to the Russian peasantry, perhaps because of their status as outcastes and oppositionists, practically all Molokan [and Jumper] men and many women have knowledge, sometimes in-depth knowledge, of the Molokan [and Jumper] doctrine and the Bible. This is one of the requirements of the unwritten zakon.

12. By Way of Conclusions

Obviously, in order for Molokanism [and Jumpers] to survive, the zakon has to be open for interpretation and allow some flexible readjustments to keep a balance not only with the needs of the individuals and their ever-changing physical environment, but also, in view of their pilgrimage, with the socio-cultural environment. Most Molokans prefer not to discuss the issue of change and modem adjustment with outsiders. Instead, they emphasize that the zakon, carefully guarded by the elders, is still strongly observed in the community,(40) even though many complain that "it is getting harder and harder to comply with." Opinions, however, vary. Those who consider a strict observance of the zakon to be necessary for the survival of Molokanism [and Jumpers] are opposed by some younger voices saying that without adequate flexibility Molokanism [and Jumpers] cannot compete with the advances in modem society.

No doubt, the inner dynamics of Molokanism [and Jumpers] contain opposing tendencies. In Molokan [and Jumper] ideal reality, the community's life is oriented toward history and tradition; historical events that took place in a distant past are recounted continuously and what happened to Molokan [especially Jumper-S&L-user] forefathers is relevant directly to the present, at least rhetorically: "We live and pray exactly as our forefathers did.” New features are introduced slowly and seemingly imperceptibly through the process of constructing the negotiated meaning. Some [Jumper-S&L-users] Molokans in Russian villages, for example, still refuse and forbid their children to watch television while many are among the first to use cars, tape recorders, and other modern technologies. In contrast, American [Jumper-S&L-users] Molokans do not object to any technology on ideological grounds. [Several Russian Jumper-S&L-user congregations shun all American S&L-users and those who associate with them.] On the whole, Molokan [and Jumper] communities appear to be open to anything in the outside world that can be useful for spiritual and economic prosperity. In Russia, it is perhaps not by chance that the Molokans [and Jumpers] were quick to take advantage of the new political and economic freedoms. It is perhaps also not a coincidence that most of the [Jumper-S&L-user] Molokan newcomers to the United States love what they call "the American way of living,” with its dynamic necessity to make choices constantly and quickly, importance of personal prosperity, and respect for professional skills. Yet, the response to the environment in most Molokan [and Jumper] communities can be described as one with a centric orientation: quickly responding to modem advantages but strictly warding off outsiders. [Many Jumper-S&L-user] Molokans do not encourage inviting ne nashi to their gatherings: most often, their beautiful and powerful singing is not known even to their neighbors. Will the new generation want — and will it be able — to continue "living in the world without being a part of it." as an old Molokan [and/or Jumper] saying suggests? Experiences of other ethnic and religious communities in the United States offer no single answer.

I sit at the festive table with the [Jumper] Molokans gathering for the house-warming ritual that will secure the well-being of a young family in its new, very American, house in Whittier, a very American town in the greater Los Angeles area. I am overwhelmed by the feeling that I have already seen it all just a few months ago, in a small South-Russian village near Stavropol', at the foot of the Caucasus Mountains. The entire order of the sobranie and the following feast seem the same as there. The hostess brings in a ten-inch tall, round loaf of freshly-made bread with a salt shaker on top of it; men and women are clothed in the same light colors and patterns as in Stavropol'; all the men have long beards. The meal unfolds through distinct courses, and their order is familiar as well: Tea, borscht, lamb stew, fruit compote, with pieces of bread spread all over the table, not on plates but directly on the table cloth. The room, with long parallel rows of tables and benches, is filled with familiar and dignified singing. The language one hears, however, is not just Russian; women's dresses and men's shirts are made from much more expensive fabrics than in Russia; as far as I can see through the window, the street is packed with American cars of all models. After a while, the singing too appears to sound somewhat different from what I heard in Stavropol'. I still find it astounding to be in the heart of the most American urban setting and in a world that at this moment appears so strikingly Russian and [Jumper] Molokan.

13. Postscript

Completed in 1994, this article imparts a particular moment in Molokan [and Jumper] history as well as a particular moment in the history of ethnomusicological studies. It also reflects a certain point in my own experience as a scholar. Certainly, the communities have changed since that time, new issues have come forth, and much has changed in my own interpretive thinking.(41) Several scholars, including myself, have since published new works on Molokan [and Jumper] culture and music. Nevertheless, to preserve the historical perspective of this study, no significant revisions have been undertaken during the final preparation of this article for print, and no references have been added to research published since 1994.

14. NOTES

1. Most of the people I interviewed requested that their names not be used in print. Throughout this article, field interviews are cited in quotation marks but without personal attribution.